The True Nature of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

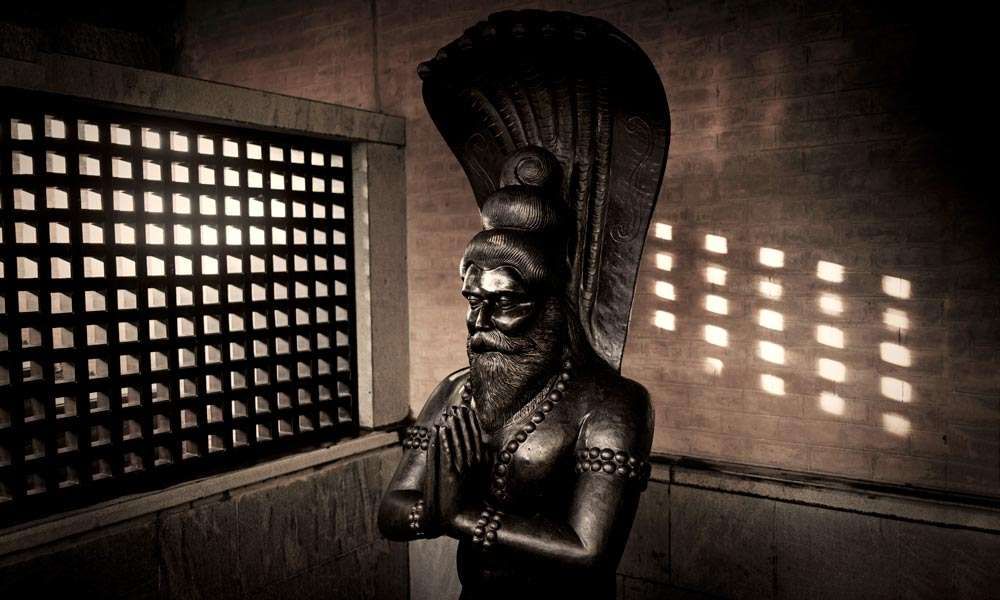

Patanjali was not only a man of many talents who wrote texts on medicine, language, and grammar, he was one of the 18 classical Tamil siddhars (sages and intellectuals), and a realized being. But he is probably most widely known as the “father of modern yoga” – not because he originated yoga, but because he distilled the essence of yoga into the famous Yoga Sutras. Here, Sadhguru sheds light on why the Yoga Sutras came into being and how to approach them. He also delves into the first two sutras, disclosing the background of the cryptic Sanskrit words that form the verses.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras – An Introduction

Sadhguru: Apart from his realization, Patanjali was a kind of intellect that would make top scientists look like kindergarten children – that is the kind of understanding he had about every aspect of life. In Patanjali’s time thousands of years ago, yoga had started specializing in such a way that there were hundreds of schools of yoga. It is like the specialization in medical science today. Thirty years ago, you just had one family doctor. Now, for every part of the body, you have a different doctor. Maybe in another fifty years, it will become like this that if you want a medical checkup, you need one hundred doctors. By the time you get an appointment with these one hundred doctors, either you are well or you are dead.Once specialization crosses a certain point, it tends to become ridiculous in terms of practicality. There is value in studying the details, but in terms of people learning and making use of it, it becomes quite ridiculous. This happened to yoga at that time – hundreds of schools handling different dimensions of yoga. Patanjali saw that it had become completely impractical, so he codified yoga in almost two hundred sutras.

The Yoga Sutras Are Not Philosophy

Today, because everyone can publish a book, there are a hundred different interpretations of the Yoga Sutras. But the Yoga Sutras are not a philosophy to be interpreted. Nor do the Yoga Sutras give any practices. They are like a scientific document. They only talk about what does what in the system. Depending upon your intention or what you want to create in the system, accordingly you design a certain kriya.

Subscribe

The word sutra literally means “thread.” A garland has a thread, but you never wear the garland for its thread. What kind of flowers, beads, pearls, or diamonds you add to it depends on the skill of the person who is putting it together. Patanjali is only providing the sutra, because without the thread, there is no garland. But you never wear a garland for the sake of its thread. So do not look at the thread and come to conclusions. The sutras are not meant to be read and logically understood. If you approach it logically, trying to understand things intellectually, it will become nonsensical.

For someone who is in a certain state of experience, this thread means a lot; he will use it to prepare a garland. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are not to be read like a book. Take one sutra and make it a reality in your life. If one sutra becomes a living reality for you, you do not have to necessarily read the other sutras.

Sutra 1: “… and now, Yoga”

The Yoga Sutras are a tremendous document on life. And Patanjali started this great document in a strange way. The first chapter of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras is half a sentence: “…and now, Yoga.” In a way, he is saying, “If you still think your life will become better with a new house, a new girlfriend, a new car, more money, or whatever else, it is not yet time for yoga.” If you saw all that and you realized that it does not fulfill your life in any way: “…and now, Yoga.”

Sutra 2: Yoga and Focus of the Mind

Questioner: Sadhguru, Patanjali’s second Yoga Sutra says, yogash chitta vritti nirodhah, which could be translated as “Yoga is the ability to direct the mind exclusively towards an object and sustain that direction without any distractions.” What does this really mean?

Sadhguru: This is called dharana. Dharana means there is you and an object, and you are entirely focused on that object. If you focus on it absolutely, after some time, only you will be there, or only the object will be there. This is called dhyana, which is the next stage of focus. If you can hold the state of dhyana, after some time, neither you nor the object will be there. There will be some other huge presence. This is called samadhi. These are progressive states of practice.

When we say, “Hold your attention on an object,” people think they have to worship a god or do something in particular. No, you can focus on a flower, a leaf, a grain of sand, a worm – it does not matter. But if you want to hold your attention on something, it must inspire a certain level of passion and emotion in you. Only then will your attention stay there. Why is it that it is so difficult for students to keep their attention on the textbook, but if there is a girl in the neighborhood that a boy is interested in, you do not have to tell him, “Think about her”? He anyway stays focused on her, because there is a certain emotion behind it.

This is the reason why the various forms of gods came in. Focus on whatever you can relate to. Maybe you cannot relate to the existing god, so you take another one. If this is not working for you, take another one. If none of them are working for you, you create your own. This is called Ishta Devata. The idea is that unless you hold something really high, you cannot maintain your focus. If you concentrate on something that you are not interested in, it will exhaust you. The focus will enhance you only when you are really grabbed by something.

It is as simple as going to a movie or reading a book. Let us say you read a textbook – the textbook is written for an average intelligence. In spite of that, you read it ten times but still do not get it. On the other hand, you read a love story or a suspense thriller at seventy pages per hour, and you remember every word of it. The object of focus must inspire passion in you. Otherwise, concentration becomes a concentration camp within yourself. It becomes suffering.

Editor’s Note: Find more of Sadhguru’s insights in the book “Of Mystics and Mistakes.” Download the preview chapter or purchase the ebook at Isha Downloads.

A version of this article was originally published in Forest Flower, August 2018.